Backstage at the Graystone

Chapter 1: ‘Wall-to-Wall People’

There was no place quite like the Graystone Ballroom.

With its vertical marquee towering above Woodward Avenue, the Graystone was Detroit’s ultimate hot spot for jazz. From the early 1920s to the late 1950s, it stomped and swayed with the music of Bix Beiderbecke, Fletcher Henderson, Count Basie and other jazz luminaries. Joe Louis, the pride of Detroit, held a huge birthday party under its roof. Duke Ellington and Charlie Parker dueled there in a battle of the bands.

An advertisement for Count Basie and his orchestra in 1938. (Image: Detroit Free Press)

Listen to Berry Gordy, founder of Motown Records, describe the Graystone he knew: “Wall-to-wall people inside and out, not letting the hot, sticky summer weather keep them from wearing the finest clothes possible, moving and grooving to the live music of Duke Ellington, Count Basie or one of the other top colored bands.”

It was a place known nationally for great jazz. Yet for all the music it generated and stars it attracted, the Graystone had a quiet backstory: “Detroit’s Million Dollar Ballroom” was the property of the University of Michigan. It was a fact rarely disclosed publicly, and one buried behind leases and sub-leases that placed control of the famous ballroom in others’ hands.

For the University of Michigan, the Graystone Ballroom is the study of a well-meaning private gift that took on a life of its own, with financial benefits that supported students and employees but at the cost of lawsuits, foreclosures, police calls and, in the end, the death of a teenage boy.

The Graystone was, in the carefully controlled words of one U-M official, “an operation that has presented difficult problems.”

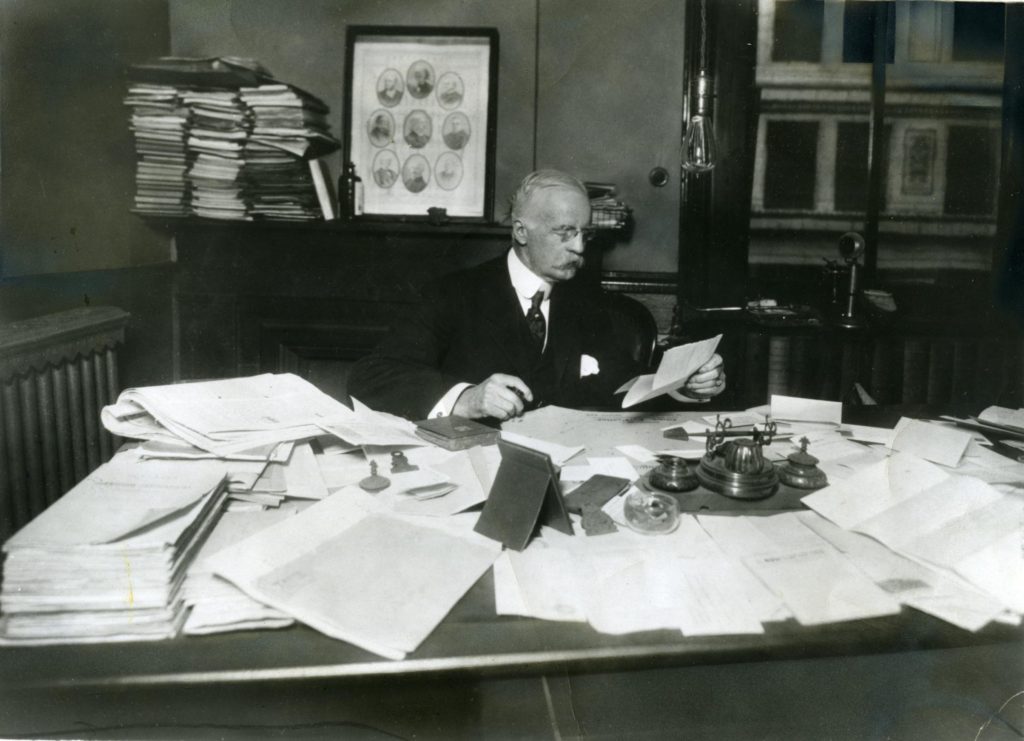

Regent Levi L. Barbour was a Detroit lawyer and philanthropist. His gift of land launched the story of the Graystone Ballroom. (Image: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan)

Chapter 2: The Gift

It would take nearly 30 years for the Graystone Ballroom to materialize from a gift to U-M.

Its roots lay in a parcel of empty land and the philanthropy of Levi Lewis Barbour, a two-time Michigan graduate and regent who made a success of himself as a Detroit lawyer devoted to civic causes. His name lives on today with Betsy Barbour Residence, which honors his mother, and the Barbour Scholars, one of U-M’s oldest fellowship programs.

When Barbour made gifts to his alma mater – which he did regularly and generously – it was often in the form of property he hoped the University would sell for cash to fund projects. He donated parcels of land, books, furniture and eventually his Detroit home.

Barbour’s giving to Michigan spanned more than three decades. His first gift came in October 1894, a patch of property along Woodward Avenue, Detroit’s grandest street. The parcel, he believed, could be converted into cash for a sorely needed campus art museum in Ann Arbor.

The regents instead sat on the land for nearly a decade before deciding that, rather than sell it, they could make better use of it by constructing an apartment building and becoming landlords. Apartment houses were a hot commodity in the city, and board members saw a good return on such an investment.

“These buildings appear to be in great and increasing demand, and when finished are quickly rented,” Regent George Farr told his colleagues after studying Detroit’s housing scene. “These appear to pay a fair, in many cases, a large, interest upon the investment.”

The Woodward location “is in the best resident district of the city and in all human probability likely to remain so.”

Farr added an important note that would have ramifications for years for U-M: “In such an investment the University would have nearly 2 percent the advantage of private owners in the immunity from taxation.” In other words, as a public entity, U-M would be ahead of its competitors because it would not be required to pay property taxes on its building.

The board voted to proceed with an apartment house, including buying up a small piece of Woodward Avenue land adjoining Levi Barbour’s donated parcel.

An unsolicited rendering of a U-M apartment house for Detroit angered local businessmen in 1903. (Image: Detroit Free Press)

Chapter 3: The Neighbors

Not so fast, said the city’s property owners.

“We, the undersigned citizens of Detroit, many of us landlords and heavy taxpayers, do hereby earnestly protest against your entering this field and putting up a tenement building in our city: and especially so, under the mistaken idea that it will not be taxed.”

For month after month in 1904, businessmen and landlords lobbied against U-M’s plans. It was one thing for the citizenry to support U-M in its work of educating students, and taxpayers already were being generous. But operating an apartment house, they warned, created a dangerous precedent.

“If the university should throw its large funds into any business and escape the taxation which others bear, it could make prices that would cut the like out of any who tried to meet them. If it can build tenements it can start a newspaper, run a factory or open a store, and become not an educational institution, but a great business organization,” they wrote in a petition to the Board of Regents.

(The regents did not help their cause by arguing that a U-M apartment building would be so splendid that rents would be in a stratosphere posing zero competition. “The structure we have in mind would be far superior to anything now in the city, and would attract only the highest class of tenants,” said Regent Frank W. Fletcher.)

Still, after months of protests, the regents quietly dropped their plans. Their next idea, driven by Regent Barbour himself, came in 1911: sublet the property and require someone else to erect a building.

The Graystone Ballroom was still a decade away.

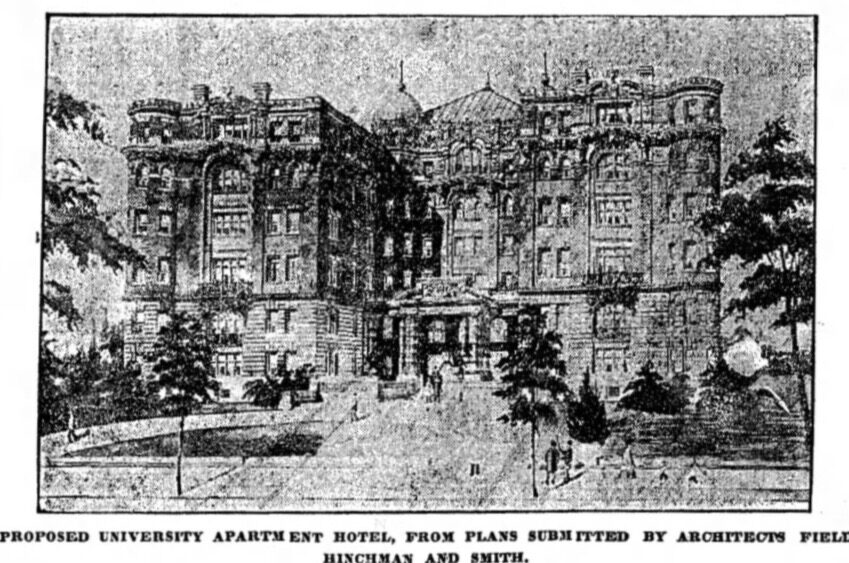

The Trocadero Hotel as advertised in early 1920. (Image: Detroit Free Press)

Chapter 4: The Chinese

The regents leased the Woodward Avenue property to Edwin S. George, a millionaire businessman who would later donate a nature preserve to U-M. It was a 40-year arrangement requiring George to construct a $40,000 building that the regents would own.

Through numerous subleases and several years, plans for a building rested with unlikely tenants: Lee Taan, Sing Get Moy and the Chinese Merchants Association of Detroit. They called themselves the Trocadero Hotel Group and their plans were nothing if not grand. (Where U-M had required Edwin George to build a $40,000 building, George in turn was requiring Taan and his group to erect a $150,000 structure.) The group now envisioned a 115-room, eight-story hotel with a $1.1 million price tag – the equivalent of $14 million today.

A local bank provided financing, contracts were let to masons, electricians, roofers and carpenters, and construction began on the Trocadero Hotel. It would feature a 1,500-seat restaurant, banquet rooms, and “the largest and finest dance floor in the city for those that dance – and music that will please.” Doors would open in late 1920.

But a problem quickly presented itself. “The Chinamen occupying one of the Barbour pieces apparently are not paying their bills,” wrote Regent James O. Murfin from his Detroit office after receiving notice of a lien placed against him.

Here came attorneys for Superior Sand & Gravel, Sibley Lumber Company, Atlas Iron and Steel, and others, all wanting to be paid for building the Trocadero. Week after week in 1920 and 1921, regents were being sued. “I am not keeping track of these items but herewith another lien against Lee Taan and Sing Get Moy filed on behalf of Red Line Cartage and Taxi Company,” wrote an exasperated Murfin when passing along yet another claim to University officials.

(“I acknowledge your letter of July 19, re failure of Chinese Republic up on Woodward Avenue to pay its bills, with consequent effort of creditors to rely upon American citizenship to take care of these items,” University Secretary Shirley Smith told Murfin. “It is the old idea of the League of Nations.”)

There was another complication. The City of Detroit was suing for property taxes and targeted Edwin George, holder of the land lease, who had refused to pay. George turned to his landlord U-M for legal help. The regents did not hesitate, in Murfin’s words, “to make sure … there was no judicial determination that property owned by the University, even tho’ used for commercial purposes, can be called upon to pay local taxes.”

The case went before Wayne County Circuit Judge George P. Codd. He knew both the city and the University; he was a U-M graduate who captained the baseball team and later served for a year as mayor of Detroit. Codd’s ruling favored his alma mater: Property held by U-M is public property and exempt from taxation.

The Chinese would default on their financing and the bank, looking to protect its investment, stepped in to see that the Trocadero was completed. It would open in late February 1922 with a new name: The Graystone Ballroom.

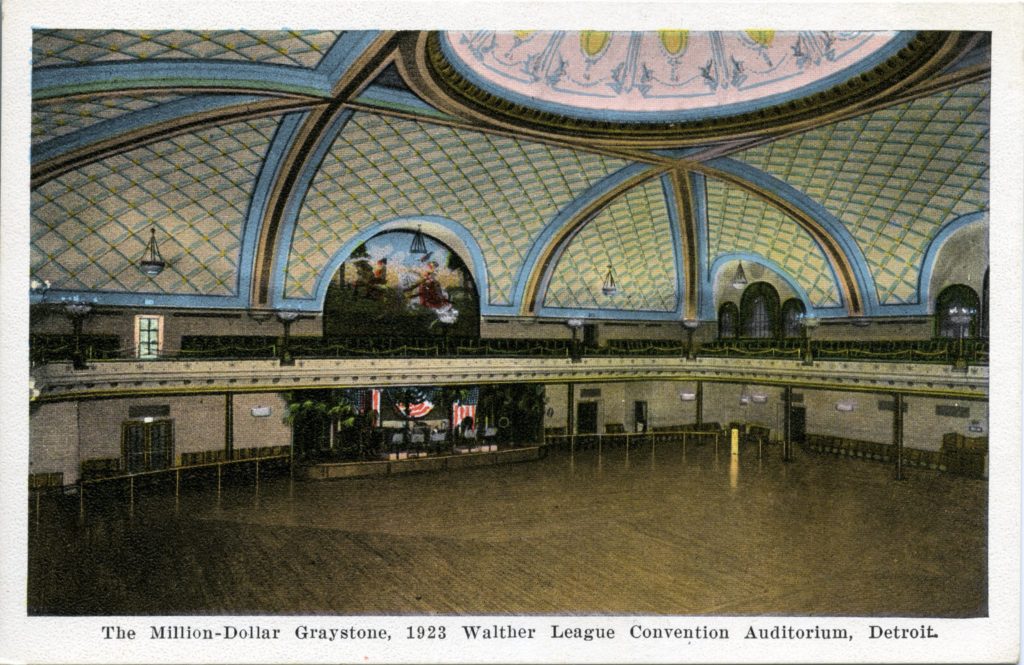

The Graystone Ballroom in all its splendor in 1923. (Image: Detroit Historical Society)

Chapter 5: The Ballroom

It was a spectacular space.

A domed ceiling soared five stories over a sprawling dance floor designed to hold 3,000 people and which, in the years to come, would see nearly twice that many crowd onto it. There was a stage for musicians, a state-of-the-art lighting system to cast color and mood, coat rooms, rest rooms and smoking rooms. A balcony ringed the dance floor, with lounge chairs and divans, and a large mural above the stage depicted an old English hunting scene.

The Detroit Free Press was effusive on the eve of the Graystone’s opening:

“One ideal has prevailed throughout the work of the owners, architects, designers and artisans of the building. That has been to make the structure one of beauty and practicability. From the outset the greatest care has been devoted to make it something more than a mass of building material forming just a hotel and ballroom.

“This ideal caused much thought, detailed work and increased cost, but now, as the building reaches the completed stage, the results show the additional care to have been amply justified.”

The great dance hall sat at the rear of the Graystone structure. The front was a five-story Gothic building with space for Woodward Avenue shops, upper-level offices, and hotel rooms. But the ballroom was the star. A number of dance halls dotted Woodward and downtown Detroit, and the Graystone was the biggest.

“The most beautiful ballroom in the middle west if not all the land. The Graystone is ravishingly beautiful,” gushed Graystone Topics, the ballroom’s in-house newspaper. “From the main entrance to the farthest corner of the spacious ballroom it is bewildering and bewitching, a maze of color as radiant and varied as the rainbow and as perfectly harmonized and gracefully blended.”

McKinney’s Cotton Pickers were a fixture at the Graystone in the 1920s (Image: Detroit News Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University)

Chapter 6: The Jazz

There is no dancing without music, and the Graystone showcased the country’s finest jazz players on its ballroom stage.

Among the first and the best bands at the Graystone were the Jean Goldkette Orchestra and McKinney’s Cotton Pickers. Goldkette himself operated the ballroom for several years in addition to leading his pioneering jazz outfit, which sometimes featured Bix Beiderbecke, considered one of the finest jazz players ever. WWJ radio carried the shows live, sharing the Graystone with listeners in Chicago, Pittsburgh, St. Louis and Philadelphia.

The band leader Cab Calloway in the early 1930s, when zoot suits were the rage. (Image: Digital Collections, The New York Public Library)

Jazz, both sweet and hot, filled the great ballroom, as did swing and big band music. The artists who graced the Graystone make for a jazz pantheon. Earl “Fatha” Hines. Louis Armstrong. Fletcher Henderson. Count Basie. Jimmie Lunceford. Erskine Hawkins. Jimmy Dorsey. Dinah Washington.

“We were in a little bit of heaven Monday night at the Graystone Ballroom. ‘Cab’ Calloway has a ‘tight’ band, and we raised whoopee and how!” wrote Milton J. Williams for the Inter-State Tattler, an African American newspaper based in New York City, in the spring of 1929.

The flamboyant Calloway would return in the summer of 1935 – now famous as the “Hi-De-Ho” man thanks to his hit, “Minnie the Moocher” – and draw 6,000 to the Graystone.

When Louis Armstrong played the Graystone on Aug. 12, 1937, he drew even more fans.

“King Satchmo, his royal highness Louis Armstrong, emperor of all trumpetdom and king of kings of all cornet players the world over Monday last, really went to town here at the Graystone ballroom. King Satchmo broke his record here of a month or so previous. His box office attendance was a thousand more than that of Cab Calloway, the Hi-De-Ho King,” wrote Earl J. Morris in filing a story from Detroit for the Pittsburgh Courier.

Like all of Detroit’s dance halls of the era, the Graystone was racially segregated. While African American musicians could perform any and all evenings, Black patrons were allowed into the ballroom only on Monday nights.

In 1934, more than 7,500 Black patrons crowded the Graystone for two men: visiting bandleader Duke Ellington and Bill Walker, a Detroit entrepreneur who managed African American halls such as Club Plantation, Club Alabam, the Chocolate Bar and the Graystone. On this night, Walker’s leadership led to his being feted as the “unofficial mayor of Detroit.”

“Here was a gala night. Duke Ellington, acknowledged as the best of the Negro jazz-band masters, came to Detroit with his pulsating rhythm, especially for the election, (which) made him officially what everyone had been calling him before. They crowned him the King of Jazz,” wrote the Free Press.

In 1943, Graystone managers announced a liquor-free policy for “the dancing and music loving public who believe in clean, wholesome entertainment.” It was a policy conveyed in less-than-subtle ways when the Graystone advertised in The Detroit Tribune, the local African American newspaper. “Let’s keep the world finest Ballroom open for Negroes to enjoy. If you can’t get in line with this policy, don’t get in line for tickets.”

Detroiter Berry Gordy was one of the young Black patrons who crowded into the segregated ballroom. “Graystone Ballroom and Gardens was where we went on Monday nights, the only night colored people could go,” he wrote in his autobiography. “That was our big night. Everybody who was anybody would be there, dressed to kill.”

Income from the Woodward Avenue Lease Fund paid for a director of the USO at U-M during World War II. (Image: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan)

Chapter 7: The Benefits

For all the big acts rolling through the Graystone, more ordinary business was being carried out in Ann Arbor using proceeds from the building’s lease. This was, after all, the objective in leasing the Barbour property: “making profitable use of the University’s lot on Woodward Avenue.”

Officials set up what they called the Woodward Avenue Lease Fund, and used the money for everything from office supplies and electric bills to student loans and, in one case, the funeral of a beloved employee. Leases changed hands and payments to U-M rose and fell through the years, and the fund typically was worth $82,000. Investment income was used to pay professors’ salaries, restore and publish books, support student groups such as glee clubs and the marching band, and entertain legislators visiting campus.

Some of the more sublime uses:

— Paying for President Marion L. Burton to travel to England in 1923 to meet that country’s poet laureate, Robert Bridges. Bridges would succeed poet Robert Frost as U-M’s creative arts fellow and spend several months on campus.

— Cheering students who found themselves sick at the University Health Service on Christmas Day, with flowers placed at their bedsides.

— Repairing and restoring the majestic Frieze Memorial Organ in Hill Auditorium in the late 1920s.

— Supporting students struggling through the Great Depression. “The past year has been a hard one for students and their families, and an unusual number of applications for student loans have been forthcoming,” President Alexander G. Ruthven told regents in 1931. Using money from the Graystone and other accounts, regents set up a loan fund for needy students.

— Ensuring a proper burial for Frances Jewett Dunbar, a 1903 graduate in zoology who devoted 30 years to making scientific slides and photographs. She both worked and lived in a small space in the West Medical Building (today’s Dana Building), with a ragtag collie named Nellie and a white rat called Dolly Gann. When Dunbar died of a heart attack at age 66 in 1934, her longtime friend and university president, Alexander Ruthven, phoned several regents for help. Dunbar and Ruthven had first worked together as lab assistants in the Zoology Department, and now he wanted the University to pay for her funeral. She was buried, with the support of the Woodward Avenue Lease Fund, in a University plot in Forest Hills Cemetery.

Downtown Detroit looms in the distance, south of the Graystone along Woodward Avenue. (Image: Detroit News Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University)

Chapter 8: The Decline

The Graystone hummed along for some 30 years, riding out Prohibition and economic downturns, a deadly race riot in 1943, and the boom of the auto industry.

There was a churn of leases and lawsuits with the Graystone. Musicians sued for unemployment and Social Security benefits. Banks holding the lease went bankrupt. The City of Detroit tightened its zoning ordinances. One renter – Lee Taan, originator of the ill-fated Trocadero – even sued for money he might have made had he not gone bankrupt. The Michigan Supreme Court tossed the case, telling Taan he “cannot take advantage of his own default.”

And the ballroom crowds grew smaller and smaller as tastes and times changed.

On Nov. 30, 1957, after a Stan Kenton show that failed to break even, the Graystone closed its doors. “We were up against a brick wall. The young people stopped dancing. And we couldn’t get them to start again,” said Francis M. Steltenkamp, president of Graystone Ballroom Inc. He blamed the rise of television and the popularity of house parties for the lack of young customers. “Whatever they do, they don’t dance.”

Steltenkamp’s company had been in charge of the ballroom for some 25 years, and had a new lease with U-M that ran through 2002. But it had been slipping on its payments for a year. Woodward Avenue was backsliding, and the population of Detroit entered its long, slow decline.

U-M’s regents now had a problem. The Graystone was built for one purpose – to be a ballroom – and renovating it into something else made no financial sense. The front of the building, with its five floors of office space, had never been completed since 1920 and was a crumbling shell. Nearby Wayne State University said it had no interest in the building. “Any plans that the City of Detroit may have for the development of this area are considered to be so far in the future that they are not a practical consideration at present,” U-M Vice President Wilbur K. Pierpont told the regents.

On Pierpont’s recommendation, the University forfeited the lease in early 1958, put the Graystone in the hands of a bank, and hoped to sell what had become a white elephant. The asking price was $185,000.

There were no bites.

After six months and “extensive efforts,” the bank had zero prospects. “It has advertised it, circularized real estate brokers and investors, and had also contacted various types of social associations and organizations that might have a use for a property of this type,” Pierpont said. “The results so far have not been satisfactory.”

U-M’s only prospect for the Graystone came in the form of promoter Howard G. Pyle. A World War II veteran, he had experience operating Detroit nightclubs and was now using dying ballrooms for boxing matches and teen dances. Pyle’s record was far from spotless. He had been arrested by Detroit police for letting minors into one of his clubs after two teenagers, intent on robbing a Woodward Avenue shop owner, shot and killed the man.

And, as Pierpont noted in recommending a short-term lease, “Mr. Pyle shows no financial backing.” The bank was underwhelmed by him.

But a ballroom with a few paying customers is better than an empty one, and a sale was going nowhere. The regents offered Pyle a $125,000 land contract that would be paid off by 1968.

Pyle began using the Graystone for boxing matches, roller skating, dances for a teen club he called “The Jolly Rogers” and the occasional name performer. Fats Domino performed one night, as did Ray Charles and Etta James. But it was never enough to keep Pyle solvent or out of trouble; he was arrested several times and jailed for letting kids into the dance hall, which by state law prohibited anyone under 17.

The regents accepted smaller and smaller monthly payments from Pyle – $3,000, then $1,500, and then $550 – and lowered the price on the building to $110,000. Still, Pyle and the ballroom fell behind on rent.

By the summer of 1962, the University was ready to unload the Graystone.

“The sale would restore the property to the tax rolls of the city of Detroit,” Pierpoint recommended, “and would enable the University to withdraw from an operation that has presented difficult problems.”

Pyle and U-M would face one more challenge.

The death of James Rickman was front page news in The Michigan Chronicle, Detroit’s African American newspaper.

Chapter 9: The Homicide

On a November Sunday in 1962, 15-year-old James Rickman went to the Graystone with friends. The teen lived five miles away, on the city’s east side, and was one of hundreds of young people crowded into the ballroom to hang out, listen to music and dance to records.

Earlier in the day, thousands had gathered along Woodward Avenue, a few blocks south of the Graystone, for the city’s annual Veterans Day parade. Old soldiers from the Spanish-American War joined veterans from Korea and the two world wars in walking down Woodward, where children on the curbsides waved American flags. The veterans ended their parade at the city center and the Michigan Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument.

Late that afternoon at the ballroom, a 17-year-old boy approached James Rickman; the two had tangled weeks earlier at Southeastern High School, with James stabbing the older boy. Now the 17-year-old wanted revenge. He punched Rickman in the face, and then slashed at him with a hunting knife. Another boy, with a razor blade, joined in the scrap. To the stunned silence of the crowd, James Rickman was soon being rushed three blocks away to Receiving Hospital.

Bleeding from a stab wound to his chest, he died less than 10 minutes after arriving, according to news reports.

It was the darkest day for a fading Graystone Ballroom.

A shuttered Graystone Ballroom. (Image: Detroit News Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University)

Chapter 10: The End

Shortly after James Rickman’s death, Howard Pyle tried selling the Graystone in Variety, the entertainment industry weekly, pitching it as a perfect place “now operating profitably.” He defaulted on his land contract with U-M, and in early 1963 abandoned plans to buy the Graystone.

By the summer, a new buyer came forward: Berry Gordy, founder of a new record label called Motown and a former Graystone patron. “I never dreamed as a kid that I’d be able to buy the Graystone Ballroom, where black people were only allowed in on Monday nights,” he wrote in his autobiography.

The University sold the Graystone for a little more than $113,000.

Gordy’s first shows at the Graystone in the summer of 1963 would feature Smokey Robinson and the Miracles and Martha and the Vandellas. A 12-year-old blind boy by the name of Little Stevie Wonder would play there alongside the Supremes and the Temptations, with a crowd of 7,000 jammed into the ballroom.

But like others who came before him at the Graystone, Gordy could not keep the building afloat. He used the building for Motown business and some shows, but by the late 1960s it was abandoned. Neglect, squatters, fire and Mother Nature ruined the building and, despite the efforts of local preservationists, the Graystone fell victim to a wrecking ball on a beautiful summer day in August 1980.

“Saying farewell to the Graystone Ballroom is hard work for the community’s older generation. But the sword wears out the sheath and even love must rest,” waxed the Free Press editors. “The good times were sweet, but age and a roof open to the storms have done in the Graystone.”

In 1998 a new building went up on Woodward Avenue. Today, the land donated to U-M by Levi Barbour is home to a McDonald’s franchise.

Sources: Board of Regents records, 1817-2011, Bentley Historical Library; James Orin Murfin Papers, Bentley Historical Library; Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer records, 1909-2016, Bentley Historical Library; Before Motown: A History of Jazz in Detroit, by Lars Bjorn with Jim Gallert; To Be Loved: The Music, The Magic, the Memories of Motown, by Berry Gordy; Bix, Man & Legend, by Richard M. Sudhalter and Philip R. Evans; Forgotten Landmarks of Detroit, by Dan Austin; and contemporary news accounts.

Originally published by the University of Michigan Heritage Project. Reprinted with permission.