‘Our Linked Lives’

Chapter 1: ‘Such a Good Friendship’

At 18, Margaret White wanted to study snakes. As a child in New Jersey she had collected garter snakes. Now, as a University of Michigan sophomore in 1923, she kept a milk snake in the bedroom of her Ann Street boarding house. She had transferred to Ann Arbor from Columbia University for one reason: Professor Alexander Ruthven, considered one of the best herpetologists in the country.

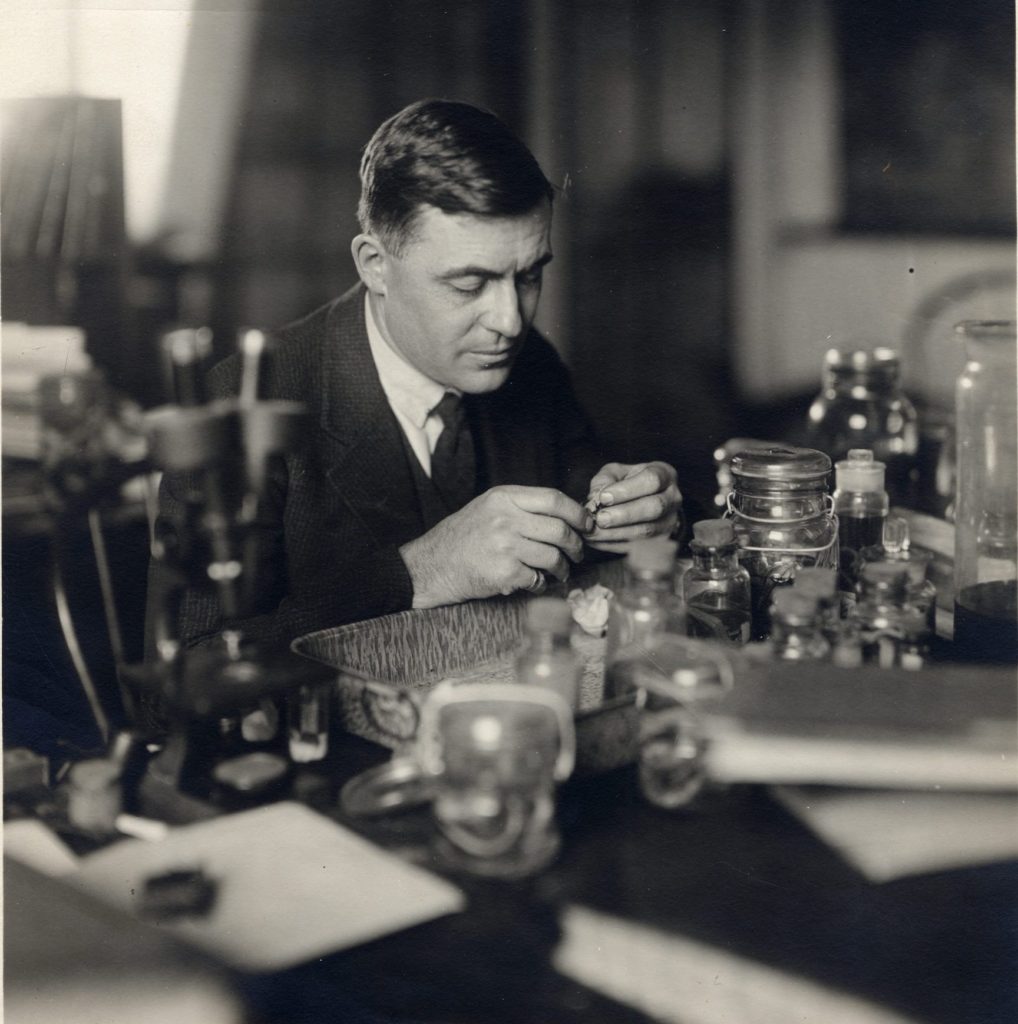

Alexander G. Ruthven, with a cigar in one hand and a turtle in the other. (Image: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan)

Ruthven was indeed a snake man. When he first came to U-M for graduate study of the geography and ecology of reptiles, Ruthven was enrolled by longtime President James B. Angell. Ruthven graduated, joined the faculty, and soon became director of the University’s Museum of Zoology. Still, when Ruthven passed the old president on campus, Angell would lift his cane in greeting. “Good morning, Ruthven. How are the snakes?”

It was now apparent to Ruthven that the young woman who stood in his office, after a few weeks of working in the zoology museum and despite her professed love of snakes, “was not the kind of clay that could be molded into a successful herpetologist.”

What, the professor asked, do you really want to be?

“I would like to be a photographer.”

He directed her to the museum’s darkroom, and thus began one of the more remarkable friendships in the history of the University.

Margaret White would become Margaret Bourke-White, one of the most famous news photographers of the 20th century, documenting the Dust Bowl, global conflict, Stalin and Gandhi, and Nazi concentration camps. Alexander Grant Ruthven would be named president of his alma mater and steer it through the Depression, World War II and a post-war enrollment boom that solidified Michigan’s prowess as a great center of research.

The photographer and president were friends for nearly 50 years. They followed each other’s careers and wrote of the other in their respective autobiographies. Bourke-White returned to campus several times, and made it clear she would come whenever Ruthven called. He kept a photo of her on his desk.

And in their final years, they shared a debilitating disease that drew them even closer. “It has been such a good friendship all these years,” Bourke-White said, “and I have drawn a lot of strength from it.”

President Alexander G. Ruthven was a noted specialist in snakes. (Image: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan)

Chapter 2: Campus Days

When Margaret White trekked to Alexander Ruthven’s office in the University Museum in early 1923, she was visiting a place he had made his own.

Ruthven was popular, and efficient, as a zoology professor and museum director; his staff revered him for his organizational skills, his knowledge of the natural world, and his dry wit. His leadership elevated both the reputation of the University Museum as among the best on a college campus and Ruthven’s status as a talented director. When the American Museum of Natural History tried to woo him away from Michigan, Ruthven parlayed it into a pay raise and promotion to a full professorship. It was one of many attempts by outside organizations to poach Ruthven.

The museum building itself was a four-story brick-and-stone creation of former architecture professor William LeBaron Jenney, who would become known as the father of the American skyscraper. Built in 1880, it stood on State Street near the south end of today’s Angell Hall. By the time Bourke-White was a student, it was cramped and Ruthven was actively campaigning for a new museum to house the collections of reptiles, mammals, fishes, crustaceans and other creatures scattered throughout several campus buildings.

The darkroom was on the fourth floor. Like everything else in the museum, it was inadequate. But it was here where Ruthven sent White – she only became Bourke-White later by hyphenating her middle and last names – to print black-and-white photographs of specimens. Her new mentor, she wrote in her diary, “is helping me on one condition, that I make a ‘world figure’ of myself. … Everybody expects so much of me – I will be a success.”

Through a 21st-century lens clouded by headlines of inappropriate conduct in the workplace, the relationship between Ruthven and Bourke-White might raise eyebrows. He was ruggedly handsome, with brooding eyes and a love of all things outdoors. She was slender, attractive and always immaculately dressed, her dark hair bobbed in the fashion of the day. Their letters through the years are rich with love and affection.

But whether it was 1923 or 1963, he was always “Dr. Ruthven.” Some 22 years separated them. When he and Bourke-White first met, Ruthven was a married man with three children. And she was falling in love with an electrical engineering student named Everett Chapman whom she would marry at the end of her junior year.

She also was learning to love photography. She joined the staff of the Michiganensian, and her photographs appeared in the 1923 and ’24 yearbooks. They are full-page architectural and landscape images capturing the Michigan Union, Hill Auditorium, Clements Library, Diag walkways and the new Lawyer’s Club. Shadows, rain and fog often figure in the images.

She and Chapman, whom everyone called “Chappie,” worked together on photography, hosting private shows on campus and selling their work. After their marriage and Chappie’s graduation in 1924, the newlyweds headed to Purdue University, where he began graduate school and she continued as an undergraduate.

The marriage did not last; by 1926 the couple was divorced. After Purdue, Bourke-White attended Western Reserve University in Cleveland and finally Cornell University, where she graduated in 1927.

All the while, Ruthven remained at Michigan.

Margaret White’s photographs filled several pages of the 1924 Michiganensian yearbook.

Chapter 3: Magical Happenings

There was a synchronicity to the lives led by Bourke-White and her mentor. While she traveled the world, and he lived in Ann Arbor until his death, the highs and lows of their professional and personal lives often seemed to run in parallel.

“There really is something to it – the magical happenings which link our lives,” Bourke-White wrote in 1963.

Consider:

In 1929, Bourke-White was hired for the job she always wanted, while Ruthven was named to a position he claimed he never sought and always regretted accepting. The work that would define each career was under way.

Henry Luce, founder of Time magazine, was starting a new business magazine called Fortune. He had seen Bourke-White’s commercial photography and wanted her for his slick new publication targeting businessmen. At a time when the price of a newspaper was two cents, Luce would charge a dollar for an issue of Fortune.

In July 1929, Bourke-White signed on as the magazine’s first staff photographer, earning $1,000 a month for a half-time position.

In Ann Arbor, the Board of Regents named Ruthven as U-M’s seventh president. A year earlier, having shown his organizational finesse as museum director, he had been appointed dean of administration, a job equivalent to a vice presidency. By 1929, unhappy with the leadership of President Clarence C. Little, the board forced his resignation and turned to Ruthven.

Many years after his presidency, Ruthven would say repeatedly that he never had wanted the job. But he felt Little’s rocky tenure had damaged a place he loved. “The University was badly disorganized, and I knew the problems, at least some of the answers, and felt obligated to the institution to which I owed so much.”

(In typical Ruthven style, he also cracked wise about the promotion. “The regents never divulged to me their reasons for my appointment. I prefer not to believe the students were right in concluding the selection was made on the assumption that a herpetologist could handle the faculty.”)

As Ruthven grew into his role, Bourke-White achieved greater and greater acclaim as a photographer. She chronicled the construction of New York’s Chrysler Building, working 800 feet in the sky to capture details. She traveled repeatedly to communist Russia, and her photos were published in the New York Times and led to a book. She photographed the devastating drought in the Plains states and the poverty of the Great Depression.

In 1936, Henry Luce started a picture magazine called Life, and again wanted Bourke-White. She was the magazine’s first woman photographer, and its debut cover featured her imposing photograph of Fort Peck Dam, a Public Works Administration project in Montana.

Her work at Life established both Bourke-White and the magazine as journalism royalty. In the days before television, Life brought the world into readers’ living rooms.

During World War II, Bourke-White would be credentialed as the first female war photographer. She survived being torpedoed when a German submarine sank a troopship she was aboard. She later flew into combat – the first woman to do so – in a B-17 Flying Fortress, watching bombs fall on German troops in Tunisia. From her vantage point, the exploding missiles were tiny red flashes.

“The impersonality of modern war has become stupendous, grotesque,” she wrote later in her autobiography. “Even in the heart of battle, one human being’s ray of vision lights only a narrow slice of the whole, and all the rest is remote – so incredibly remote.”

It was far less remote for Ruthven. In the early days of the war, he would find himself in London during the Blitz, witnessing firsthand the destruction wrought by nighttime German raids. He wrote to his granddaughter: “This is your first letter from London and it is being written while antiaircraft guns are booming like thunder. I hope when you are grown up this terrible foolishness is looked upon for what it is – just plain barbarism. I do not want you to have to listen to the scream of a bomb.”

After atomic bombs ended the war, Bourke-White signed on as a sponsor of Ruthven’s Michigan Memorial Phoenix Project, a research initiative to explore peaceful uses of nuclear energy.

Margaret Bourke-White receives an honorary degree during Michigan commencement in 1951. (Image: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan)

Chapter 4: ‘With Greatest Happiness’

Alexander Ruthven served as U-M president for 22 years – second only to the president who registered him for graduate school, James B. Angell, with 38 years of service. His presidency saw the student body grow from fewer than 10,000 to nearly 23,000 and the construction of Burton Memorial Tower, the Rackham Building, and the Stockwell, West Quad, East Quad and Alice Lloyd residence halls.

When Ruthven presided over his final commencement in 1951, among those sharing the stage with him at Michigan Stadium was his favorite former student.

Earlier in the year, he wrote Bourke-White with an invitation to attend graduation and receive an honorary degree. Her response came by Western Union telegram: “Accept with greatest happiness.”

A year later, with President Harlan H. Hatcher leading spring commencement, Ruthven acknowledged a letter from Bourke-White.While we do not have her letter, she must have written to say she was thinking of Ruthven at a time when, after so many years, he would not be on the dais. Ruthven demurred, saying he did not miss the routine duties of office. Students, however, were another matter.

“As I look back over the years I am impressed with the fact that the things I tend to remember most are the experiences of some of my students. I think I have been most fortunate in having those with whom I have worked continue to feel that our relationships were something more than the formal one of a student and teacher.

“At the same time I must confess that some of my former students have always been much more in my mind than others, and of these you know, I am sure, that you have been one of my favorites. I have been very proud of your accomplishments and take great pride in the fact that, although not seeing each other very often, we have continued our personal friendship.”

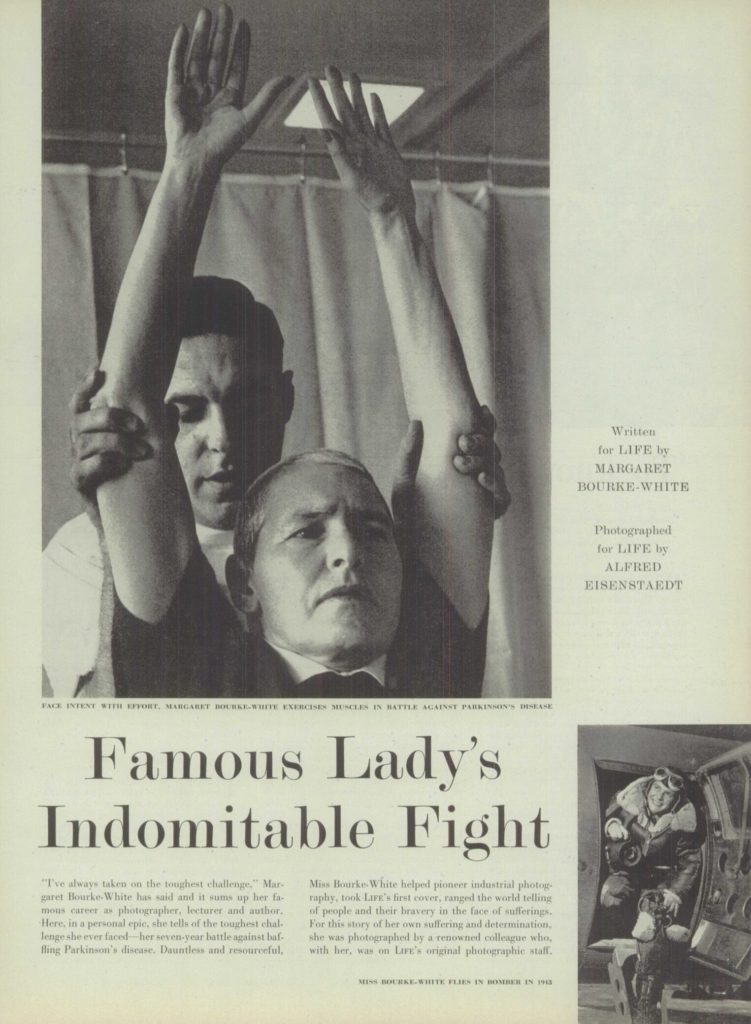

After years of confounding symptoms, Margaret Bourke-White underwent experimental brain surgery in 1959 to fight Parkinson’s disease. (Image: Alfred Eisenstaedt, Life magazine)

Chapter 5: ‘My Mysterious Malady’

In the early summer of 1959, Life magazine published an extensive photo essay about its famous photographer.

It can be difficult today to grasp the impact and influence of Life in the 20th century. It was the gold standard of photojournalism, and the best-selling weekly magazine in the nation. In 1959, it had 6.2 million subscribers. Many more bought the magazine at newsstands or read copies purchased by others.

So when the June 22 issue carried news about Margaret Bourke-White, her previously private battle with Parkinson’s disease, and an experimental brain operation she had undergone to combat it, readers took note.

One of those readers was Alexander Ruthven.

“As you might know I would be, I was very much concerned when I learned of your difficulties. … I wish I had known earlier of your illness, for while I would have been troubled, I would have tried to send you some words of encouragement.

“While we have not seen each other too often through the years, I have always felt that we were quite close in spirit. May I hope that you will let me know now and then how you are progressing.

“With my love and best wishes.”

What is just as pronounced as the sentiment of Ruthven’s letter is the signature that ends it. It is a rickety mess.

For some 20 years, Ruthven found himself fighting a palsy that shook his head, hands and voice. He was largely successful in pushing down the tremors, according to his biographer, Peter Van de Water. Ruthven would use both hands to lift a glass, which he always made certain was only half full to avoid spills. When giving speeches became a challenge, Ruthven taught himself to speak only when exhaling, allowing the energy of breathing to help carry his words.

In her autobiography, Bourke-White said Ruthven suffered from Parkinson’s disease. Ruthven’s physician, Dr. H. Marvin Pollard, said the tremors were a “familial palsy” but not Parkinson’s. Regardless, in his letters to Bourke-White, Ruthven wrote of “our burden” and said he had struggled for years. When she asked about how he handled public speaking, something she was now having difficulty with, Ruthven confessed: “You may get some amusement out of my experience when I tell you that our chief neurologist helped me years ago by recommending two martinis before every talk.”

Bourke-White first began to notice something was wrong shortly after attending U-M commencement in 1951. A dull ache in her leg. A slight stagger when standing after sitting. More aches in more limbs, the constant dropping of her gloves, and then an inability to type. She called it “my mysterious malady.” Once diagnosed, she agreed to surgery that would deaden part of her thalamus in hopes of reviving some motor skills.

Her friend and photographer Alfred Eisentaedt, who had shared the red-and-white Life masthead with her since the first issue, chronicled her recovery in nine pages of images. Her hair was just beginning to grow back after surgery; she is shown practicing knee bends, crumpling paper into balls, and enunciating words. In an accompanying essay, Bourke-White described Parkinson’s as being “on an escalator which was moving down while I was trying to run up.”

It was a humbling self-portrait by a woman who had once scaled a New York City skyscraper.

Ruthven both counseled and consoled his former student.

“It is my opinion that the best thing we can do with our problem is to live with it and try to keep it out of mind as much as possible. Do not get discouraged that walking is still difficult. It will improve if you do not think too much about it.

“I don’t know if this letter will be of any help, but at the least it will let you know that there is someone who always has you very much in mind.”

Once retired, Alexander Ruthven devoted himself to raising Morgan horses. (Image: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan)

Chapter 6: ‘Continue the Struggle’

Bourke-White’s brain surgery was followed by a second, similar operation, and both procedures brought some relief, albeit temporary, by loosening her stiff limbs, fingers and spine. Ruthven busied himself in retirement raising Morgan horses. As a child he fell in love with the animals as they pulled covered wagons westward across his native Iowa, and later he was the first to introduce the breed to Michigan.

Correspondence between the two friends was honest and open about the challenges of everyday life and concern for each other.

November 6, 1961

Dear Dr. Ruthven:

I’ve been thinking of you and wondering how you are.

As for me, I have been doing very well since the second operation last January. Of course, I don’t let up on my exercise program for a single day, but it is certainly worth it. I’m better in a good many ways than I have been for some time. No freezing to chairs anymore, or getting stuck in corners; and all my movements are much freer. I have had some trouble with my voice, but I am working with a speech therapist and my speech is improving.

Best of all, I fell (sic) extremely well and full of confidence.

My happiest achievement is to learn to jump rope. It’s funny when a silly little thing like that seems so important, but I feel that it shows a good deal of coordination. I had been working away at it during the summer, and after repeated failures, I woke up one morning, picked up my rope and jumped rope. It was as though a childhood memory came back. I have been adding one or two jumps each day. My latest record is 47 jumps without missing.

I hope you are having a beautiful Fall. Ann Arbor, I think, is the loveliest place in the world to see the autumn coloring. I hope, most of all, that everything is well with you.

With love,

Margaret

December 6, 1961

Dear Margaret:

There must be something in telepethy (sic). I have been worrying about you since your last sojourn in the hospital. I am of course delighted that you are doing so well.

I was disappointed that in your recent letter you made no reference to your new book. I hope you will be able to keep after this task. I am sure the new work will be just as interesting as your other books.

I don’t know much news from Ann Arbor that I think would be of particular interest to you. I am afraid that you would not be as pleased with your university as you have been if you could see how it has mushroomed. Ann Arbor which you have always loved is, however, this fall as beautiful as you have known it.

I am sorry that we don’t live nearer each other. I would certainly like to see you skip rope. If you are again getting to be as energetic as you used to be you will soon best your latest record of 47 jumps. As usual, you have inquired about me. I am not jumping rope but I can still ride a horse. Two or three times a week I also find time for another form of exercise somewhat different than the kinds you are enjoying. I help the manager of my little horse farm clean the stables. Now when you are hopping around with your rope you can visualize me back where I started, as my manager says, taking care of horses.

It will be news to you that I am also working on something like a book. For years my friends at the University have been pestering me to write my recollections of my long and checkered career. I have until this year been able to resist the pressure and I regret very much that I finally yielded. I find the task much less interesting than the writing of scientific papers which as you know I always enjoyed.

The other day I thought of something that I might do for historians which I probably should take up with you. You know I have a perverted sense of humor which I have to suppress many times. I still think it would be amusing if I left your letters and copies of mine to you in the University archives. In the future some ambitious candidate for the Ph.D. in History could then publish a thesis on our relationship. This would perpetuate our names which possibly in some realm we could enjoy listening to some professor convey to his classes.

I hope my dear you will continue the struggle. If I get any more bright ideas that might intrigue your interest, I will let you know.

Always with sincere admiration and devotion.

Yours sincerely,

AGR

Stiffened by Parkinson’s disease, Margaret Bourke-White makes her way through the Engineering Arch in 1970. (Image: Stu Abbey, The University Record, University of Michigan)

Chapter 7: Twilight

Margaret Bourke-White was a frequent visitor to campus through the decades. She supported her sorority, Alpha Omicron Pi, and the Alumnae Council. She spoke at the Michigan League and Hill Auditorium. “I can say that I owe quite a debt to the University of Michigan for two reasons,” she said during one appearance, “because of the invaluable photographic experience I gained from the Michiganensian as an undergraduate here, and because of the fact I studied science.”

In 1962, she was invited to attended a massive 80th birthday dinner for Ruthven, thrown by alumni and friends and staged in the ballroom of the Michigan Union. Bourke-White was unable to attend – she loaned her name to the planning committee – but sent a telegram. Ruthven said it was the “nicest feature” of the evening. He also shared that while the dinner actually took place two months after he turned 80, it fell precisely on Bourke-White’s birthday.

“You will agree, I am sure, that fate seems to have taken a special interest in our lives,” he wrote. “Something must have inspired the alumni to move my birthday to yours. It is one more happening which links our lives.”

The following year, both Ruthven and Bourke-White published autobiographies. Her book, Portrait of Myself, arrived in Ann Arbor just as Ruthven was autographing Naturalist in Two Worlds to send to her in Connecticut.

She enjoyed his memoir. “I knew, of course, that I would, but I was totally unprepared for the account on pages 20 and 21 of the young lady who visited your office and told you she would like to become ‘a news photographer-reporter and a good one.’ And you tell of your advice to her. It has been such a good friendship all these years and I have drawn a lot of strength from it.”

They had continued to compare notes and advice on living with Parkinson’s disease.

“It is my earnest hope that life is not being too rough for you and when I say this, I am sure you realize how much I mean it,” Ruthven wrote.

Bourke-White’s last visit to Ann Arbor came in the fall of 1970, the centennial of the admission of women to U-M. The Museum of Art staged an exhibition of photographs by one of Michigan’s most famous female students. Here was the best of Margaret Bourke-White, displayed within a stone’s throw of the site of one of her earliest darkrooms. (The old University Museum, where she and Ruthven had met, had stood just north of the art museum.) Across campus, the massive Museums Building, built four years after she left U-M as an undergraduate, carried Ruthven’s name.

Her visit was not publicized in advance. By the late 1960s, she could barely walk, had great difficulty speaking and required near-constant assistance. Still, “it was such a joy to be on campus again,” she wrote U-M President Robben W. Fleming.

Bourke-White spent two days in Ann Arbor. We do not know if she met with Ruthven during her visit; her physical disabilities may have been too much of a challenge. He undoubtedly would have welcomed her. He lived in a house along Fuller Road; the nearby stables where he had kept his beloved Morgan horses were gone, sold to make way for a new Ann Arbor high school. And Ruthven was lonely; his wife, Florence, had died two years earlier, and friends felt he was lost without his partner of 60 years.

The ties that so often bound Bourke-White and Ruthven in life also linked them in death. They would die six months apart, in 1971. He was 88, and passed away at home, alone and sitting in front of the television. Her death at 67, brought on by complications from a fall, was reported on the front page of the New York Times. On its editorial page, the Times paid her tribute: “If the photograph record she made was often uncompromising and blunt, it was also sensitive and straightforward. These qualities put her in the top ranks of American photographers.”

For all the years and friendship between them, there is no known photograph of Ruthven and Bourke-White together.

Sources: The Alexander G. Ruthven Papers at the Bentley Historical Library; the Margaret Bourke-White Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries; Margaret Bourke-White: A Biography by Vicki Goldberg; Portrait of Myself, by Margaret Bourke-White; Alexander Grant Ruthven: Biography of a University President, by Peter E. Van de Water; Naturalist in Two Worlds, by Alexander G. Ruthven; and Margaret Bourke-White: The Early Work, 1922-1930, by Ronald E. Ostman and Harry Littell.

Originally published by the University of Michigan Heritage Project. Reprinted with permission.