Tom Harmon is Missing

Tom Harmon’s legs were on fire.

These were the legs that had carried him and a football into the Michigan end zone time after time, racking up touchdowns and making him the leading scorer in the country. Legs that pumped across thousands of yards of turf, pushing him through the outstretched arms of Badgers and Hawkeyes and Buckeyes who could not stop him. Legs that held him ramrod straight on a New York dais in 1940 as he accepted the Heisman Trophy as the best college football player in the land.

Now, the greatest player in Michigan history was being burned alive from the legs up in the cockpit of his World War II fighter. A dogfight with Japanese pilots had exploded the plane’s fuel line. He reached down between his knees and swatted at the fire. Flames bit at his arms and face as the wounded plane plunged toward the earth. He needed to eject or he would die.

Popping the fighter’s canopy, Harmon was sucked from the cockpit into the sky. He was somewhere over Japanese-occupied China, near Jiujiang and the Yangtze River. Tumbling downward, he yanked the ripcord of his parachute. Japanese fighter planes roared by, firing their guns at him as he floated toward a lake.

His scorched legs hit the freshwater. With his parachute billowing around him, Second Lieutenant Tom Harmon sank beneath the surface.

Harmon dominated college football for three years as a Wolverine running back. (Image: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan)

Chapter Two: Harmon of Michigan

Tom Harmon was the archetypal big man on campus. And beyond.

In the final game of his remarkable collegiate career, he stepped onto the field of Ohio Stadium in Columbus. Over the next three hours, he ran for three touchdowns, threw for two more, and kicked four extra points to carry Michigan to a 40-0 trouncing of the Buckeyes. In the words of one sports columnist, “Harmon did everything and anything.”

At the end of the game, the 73,648 Ohio State fans – after suffering their worst defeat in 35 years – rose to their feet and gave Harmon a standing ovation. They then tried to tear Harmon’s jersey from his body, hoping for a souvenir of No. 98.

In addition to being an All-American in football, Harmon played varsity basketball and ran for the track team.

In his final months as a U-M student, Harmon appeared at banquets, was a guest on radio programs, and lent his name to advertisers such as Royal Crown Cola (“my taste-test winner”). He was invited to have lunch with President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He signed with Hollywood to star in a movie about himself, earning $13,500 at a time when the average factory worker brought home $1,700 a year.

With his movie earnings and soon-to-be new job as sports director at Detroit’s WJR radio, he made plans to build a grand home for his parents, a two-story brick house in the tony Ann Arbor Hills neighborhood that today is valued at $1.1 million.

He was 21 years old and a superstar.

Fame brings fans, but it also generates critics and cynics. A Michigan Daily writer joked about forming a new organization called HTHOGP – Hate Tom Harmon on General Principle Club. And editors of the Michiganensian yearbook tweaked him as “overglorified” in Tripe, the yearbook’s “weakly news” section.

“Not all milk and honey, however, was this deluge of fame and fortune, even in the Ace’s stamping ground. Many a sour grape was mouthed in memo of the ‘Hoosier Hammer’s’ academic lassitude, personal vanity, private life. Many were the lucrative offers turned down by radio-minded Thomas D. Twenty-one and physically eligible, the government may yet get him at $21 per month.”

Uncle Sam did, indeed, want Tom Harmon.

Tom Harmon and his plane. (Image: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan)

Chapter Three: Becoming Lieutenant Harmon

The United States was not yet at war, but President Roosevelt instituted a peacetime draft in 1940. When Harmon’s draft board in his hometown of Gary, Indiana, called him in July 1941, just weeks after he graduated, the football star successfully asked for a deferment. He said he was the sole support for his parents Louis, a retired steelworker, and Rose, a homemaker. Two months later, the draft board was not as understanding.

But rather than be inducted into the Army and serve as an infantryman, Harmon applied to enlist in the Army Air Corps. He did so with the blessing of the Rev. Francis McPhillips, a priest at St. Mary Student Parish where Harmon worshipped. “I know him to be of high moral character,” McPhillips told the Air Corps.

Arthur Van Duren, head counselor in the College of Literature, Science and the Arts, also vouched for Harmon. As an LSA student, Harmon had majored in English, with plans to be a radio broadcaster. He was not the strongest student academically, in part because he was busy being Tom Harmon; Bs and Cs filled his report cards. But Van Duren believed he was perfect for the Air Corps because of his leadership skills.

“He has a keen and active mind that assimilates new material and new things readily,” Van Duren told a recruiter. “His varied experiences have made it very easy for him to adapt himself to new and unusual conditions and situations.”

It was an endorsement that would be tested once Harmon was in the air. He was sent to flight school and would become a pilot, the most coveted of positions in the Air Corps.

Harmon is surrounded by his “Little Butch” crew members, all of whom died in a 1943 crash. (Image: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan)

Chapter Four: Missing in Action

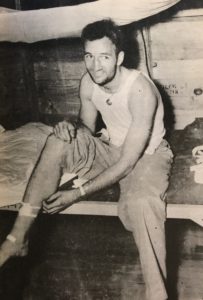

Harmon shows off his wounds after emerging from the South American rainforest. (Image: Pilots Also Pray)

In the days before his plane was shot down in late October 1943, Harmon wrote to his mother. He was diligent about sending letters to Ann Arbor, where his parents had settled into their new home on Vinewood Avenue. At the time, he was stationed in North Africa, learning to fly a P-38 Lightning, a nimble twin-tailed fighter used for escorting and protecting bombers in combat.

Harmon loved handling the P-38. It “purred like a kitten” and made tight, swift turns in the sky. His jersey number, 98, was painted on the sides. One drawback, however, was the cramped cockpit, especially after a long flight. There simply was no room to stretch his 6-foot frame. “Sometimes you have to be pulled out of the plane bodily, because your legs have gone to sleep and have the prickles so badly they won’t work, and there is nothing you can do about it.”

But he was eager to see action in China, which Japanese forces had invaded six years earlier.

“Don’t worry, Mom, I am going on a fine adventure. I have the good fortune to be with a bunch who are not only fine pilots, but fine men,” he wrote. “Keep saying those Hail Mary’s and I’ll be home before you know it.”

His parents had reason to worry. Earlier in the year, Harmon had crashed in Dutch Guiana at the northern tip of South America while en route to North Africa. Piloting a B-25 bomber, Harmon was flying with five other men through a thunderstorm when the plane’s right wing tore away. The entire crew bailed out, with Harmon parachuting into a jungle. He spent days in the rainforest, fighting insects, razor-sharp grasses, hunger and thirst. He dodged lizards and crocodiles. Pushing through ropy vines and dark swamps that stretched for miles, he eventually collapsed.

“I just didn’t have it. I fell to my knees and prayed for all the strength I could muster,” he later recalled. “I was worried about Mom. By now she must have got that telegram from the War Department. I had to get out, I just had to get out.”

After five days in the jungle, Harmon was rescued by local residents at the edge of the rainforest. He learned he was the lone survivor of the crash. He spent two weeks in the hospital recovering, and credited his “football legs” with saving him. “It is just a tangle of vines, stumps and grass, all intertwined. They wrap around your legs and pull you back … I had to have good legs to get out of there.”

Now he was preparing for China, with a new plane and a mission to take out Japanese supply ships and warehouses sitting on the Yangtze River.

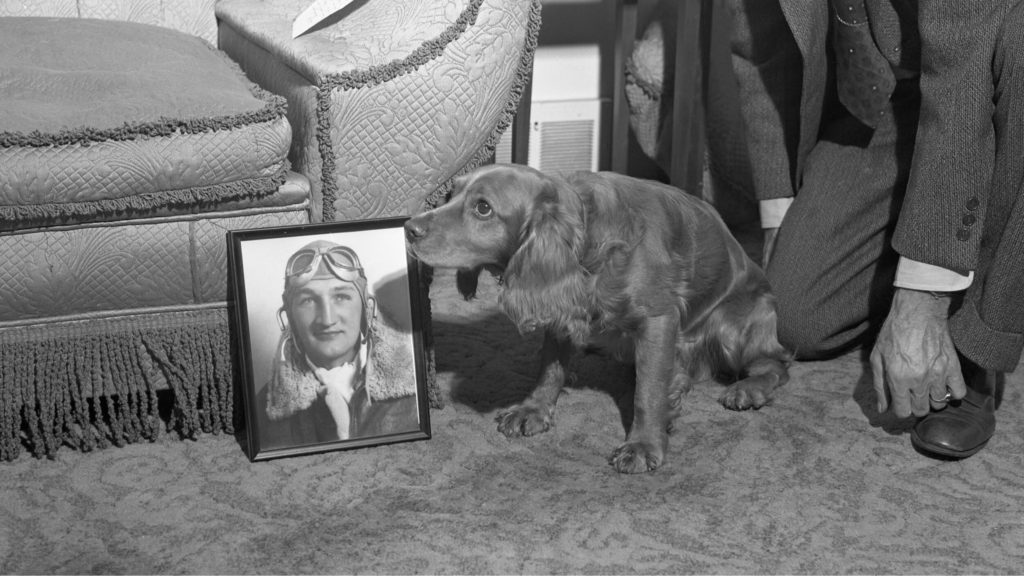

Waiting for Harmon to come home to Ann Arbor. (Image: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan)

Chapter Five: Lightning Strikes Twice

The campus paper kept track of Harmon’s wartime activities. (Image: The Michigan Daily)

When Harmon was reported missing in action for a second time, it gave family and friends pause. The pilot had been profoundly lucky to survive the South American crash. Being shot down over China presented new challenges, namely an occupying Japanese army known for its brutal treatment of prisoners of war.

“They say lightning never strikes twice in the same place, but we’ve had more than our share,” Louis Harmon said.

U-M Athletic Director Fritz Crisler, who coached Harmon and was particularly close to him, kept vigil at the Harmon home on Vinewood. “I live in the hope that he is down and all right.”

A month earlier, the war had claimed Ohio State star quarterback Don Scott in a bomber crash; Iowa halfback Nile Kinnick, who won the Heisman a year before Harmon, was killed in a June training flight. The Michigan Daily wondered: Was Harmon’s disappearance an omen? “Fatalities have a peculiar tendency of coming in threes.”

Telegrams and letters poured into the Harmon home with words of support and encouragement. Harmon’s siblings returned home to support their parents, who attended mass at St. Mary’s every morning. Reporters checked in regularly. Chinese students on campus, knowing the area where Harmon had crashed, feared the worst – he would be nowhere near friendly forces.

Harmon, of course, was hardly the war’s only casualty. In the Michigan Alumnus alone, combat deaths were a regular, somber feature. Navy Lieutenant Paul Savage Durfee, whose father Edgar was on the Law School faculty, died in the South Pacific. Rex K. Latham, a 1940 alum and a captain in the Army Air Corps, was killed in a stateside training flight. Army Lt. Alfred W. Owens, business manager of the Michiganensian, was killed fighting the Japanese in the Aleutians. Lt. John P. Ragsdale Jr., an aspiring poet who won a Hopwood Award as a student, was shot down during a bombing run over Germany in May.

It drove the cynics who had muttered about Tom Harmon’s celebrity when he was a football player to rise again when he was reported missing in China.

“We pass on to you several remarks overheard at a breakfast conversation, on campus and in a classroom,” wrote the Daily sports editor. “The most-repeated one seemed to be, ‘What! Harmon in the headlines again!” Or ‘Has Harmon scored again?’ Or ‘I see football is again saved for posterity.’ Or ‘Is Harmon more important than the war?’ Or ‘There’s that man again!’ Or ‘Let’s fall on our knees before Allah. Our hero is saved again!’

(At the same time some were sniping about the China crash, others were fixating on Harmon’s earlier disappearance in South America. Rumors swirled that Harmon had abandoned his crewmates over Dutch Guiana. Arthur Vandenberg, Michigan’s powerful Republican in the U.S. Senate, went so far as to ask Secretary of War Henry Stimson to come to Harmon’s defense; Stimson obliged, calling it “unfortunate that a young man of the high type of Tom Harmon should be the subject of such a malicious whispering campaign.”)

Other editors at the Daily had little patience for Harmon critics. “Is he to blame for becoming page one copy for every Midwest editor? Why should he take the brunt of this abuse? There is no reason in the world. It is only those shallow thinkers who can’t see beyond the edge of their book or the end of their pencil.”

The Detroit Free Press was more succinct and less dramatic. His disappearance merely symbolized what thousands of families were experiencing throughout the war. “There is no real difference between Tom and the others. He simply happens to be better known.”

Rose and Louis Harmon read the official notification that their son is safe in China. They’re flanked by their daughter, Sally Jensen, and Michigan’s Fritz Crisler. (Image: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan)

Chapter Six: “His Magnificent Fortitude”

The first photo of Harmon to appear in U.S. newspapers after he was rescued showed his weight loss. He referred to himself as a “scarecrow.” (Image: Associated Press)

On the last day of November 1943, newspapers across the country announced the unexpected: Tommy Harmon Foils Death Second Time. After disappearing on October 30, Harmon was reported safe and back at his Chinese base.

“It’s been a longer siege this time,” said Rose Harmon. “And I was beginning to think that we wouldn’t hear from Tom again.” In the days that followed, she would repeatedly and quietly offer “Thank God” to anyone listening.

Harmon never publicly discussed the details of the 30 days he was missing. In news interviews, he deflected and cautioned that divulging any information could endanger other airmen. In his autobiography, Pilots Also Pray, he devoted all of one paragraph to his injuries and rescue, in contrast to the 20-plus pages he devoted to his South American crash. With China, he was blunt: “I went through the most physically painful experience of my life.”

The flight surgeon who treated Harmon filled in the details.

After falling into the lake near Kiukiang, Harmon stayed underwater until Japanese fighter planes peeled away; he used his parachute as cover when he surfaced for air. Chinese guerillas rescued the downed pilot, who was in shock and physical agony from his burns. As the guerillas carried him on a homemade stretcher along mountain trails, Harmon’s first- and second-degree burns became infected, oozing pus and crusting over. His legs were the worst, with burns stretching from the tops of his feet to his thighs. Harmon grew increasingly delirious.

His lips and mouth, burned by flames, swelled shut and made it nearly impossible to eat. He survived sipping tea and rice fed to him by the Chinese as they walked several hundred miles. Amoebic dysentery raged through his body. It went on this way for weeks.

“The patient did not receive the benefit of medical attention for nearly a month,” wrote Major John K. Burns of the 449th Fighter Squadron. “Lieutenant Harmon managed, with his magnificent fortitude and what must have been prodigious stamina, to carry on until he was at long last delivered into the hands of his commanding officer at base.”

Harmon had lost 52 pounds – more than 25 percent of his body weight – and was thin to the point of gaunt. No matter. He became a symbol of hope and courage for American families. War Department telegrams about sons and husbands missing in action did not mean a death sentence. “Our boys are not in this war to die,” proclaimed the Philadelphia Enquirer. “It’s not going to defeat the Tommy Harmons.”

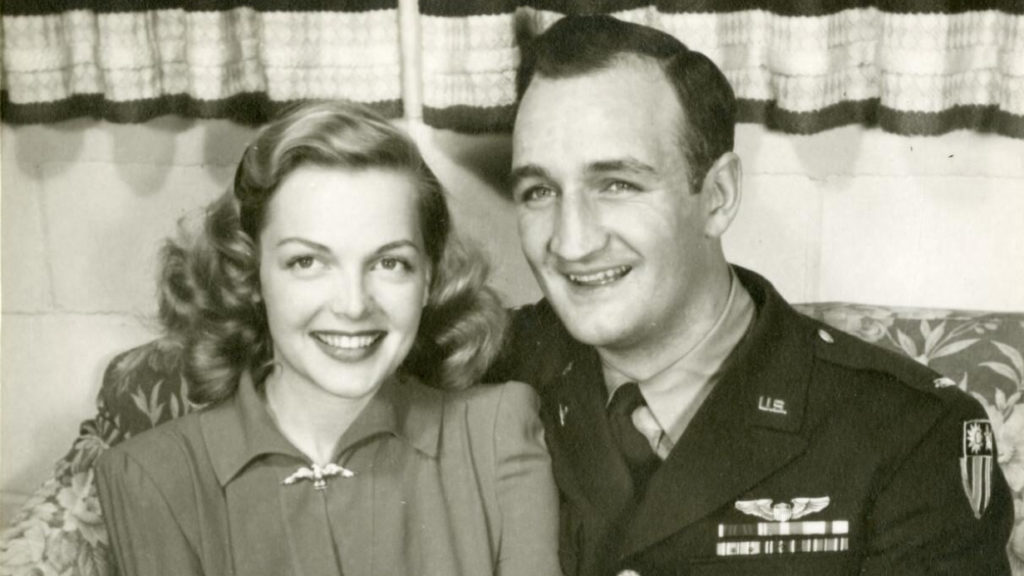

Harmon married actress Elyse Knox in 1944. (Image: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan)

Chapter Seven: End Game

Harmon was hospitalized for two weeks, telling his parents, “My old pep and zip aren’t with me as yet, but the rest I’m getting will bring it back in a hurry.” He was relieved of his flying duties and ordered back to the United States, where he received the Silver Star for his aerial combat above the Yangtze.

His famous legs healed, but his body was never quite the same due to injuries and time. He played professional football for two years after the war, but never showed the same flash as in his college days. He turned to the career he had pursued as a student and became a successful sports broadcaster in radio and television.

After surviving two plane crashes and before the war ended, Harmon married actress Elyse Knox in an Ann Arbor wedding that drew hundreds of fans outside St. Mary Chapel and later the Michigan League, where the newlyweds held their reception. It was Knox whose nickname, Little Butch, had adorned both of Harmon’s warplanes. When she walked down the aisle, it was in a wedding gown made with the silk of Harmon’s parachute from China.

Sources: Official Military Personnel File of Thomas D. Harmon; Pilots Also Pray, by Tom Harmon; The University of Michigan in China, by David Ward and Eugene Chen

Originally published by the University of Michigan Heritage Project. Reprinted with permission.